Known as a consummate colorist in her brilliantly hued painterly abstractions, Emily Mason died on December 10, 2019, age 87, at her home in Vermont after a prolonged battle with cancer. December 10 is the birthday of her favorite poet, Emily Dickinson, and Mason regarded each of her paintings as a visual poem, aiming for the expressive, and—dare I say—spiritual quality that she found in Dickinson’s verse. Mason, however, would never admit such lofty ambitions for her art. Although her artistic ambition was obvious to me and to others around her, in the passion for painting that she exuded, and the monumental body of work she produced, Mason always maintained a consistently sincere degree of modesty—sometimes bordering on unwarranted self-effacement—about her goals and achievements.

At issue was not just her struggle as a woman artist in the male-dominated milieu of the mid twentieth-century art world, but the fact that she had been surrounded by formidable artistic personalities her entire life. We worked together for years on two books exploring her life and art: Emily Mason: The Fifth Element (2006), for the legendary art-book publisher George Braziller; and Emily Mason: The Light in Spring (2015), published by the University Press of New England. Both were joyous projects, and it was gratifying to see how, in the process of examining her life and reflecting upon her long career, she was able to overcome self-doubt to some degree, and gain a new level of confidence in herself and her work. During those times, going through her archives, she was always full of wit and humor. She often poked fun at me, saying that I was trying to get her to “toot her own horn.”

Mason was born on January 12, 1932, into an artistic family. Her mother was a pioneering abstract painter Alice Trumbull Mason, a descendant of John Trumbull, a renowned portrait painter of the nineteenth century. Her father, Warwood Edwin Mason, was a captain of a commercial shipping company, and was often away at sea. Emily, therefore, grew up in a more or less matriarchal household, which brought her close to the circle of avant-garde artists surrounding her mother, a co-founder of the American Abstract Artists (AAA) group. Emily recalled that Piet Mondrian would come by for lunch. Josef Albers and Ad Reinhardt were frequent visitors, and Milton Avery would babysit her. As an adolescent during World War II, she would watch Joan Miró paint in a studio next-door to her mother’s, which he had rented during the war years.

In 1950, Emily won a scholarship to attend Bennington College, where she studied with Paul Feeley and Dan Shapiro. A 1956 Fulbright grant enabling her to study in Venice initiated a lifelong love of Italy, which she subsequently visited for extended stays nearly every year. She had a deep knowledge of Italian Renaissance art, and in our conversations, she much preferred to discuss, for instance, the color and line used by early greats like Cimabue, Giotto, and Duccio, rather than some of the contemporary art issues I tried to steer her toward.

While abroad in 1957, she married painter Wolf Kahn, who she had met earlier in New York. The couple raised a family, and remained together for the rest of her life. In 1959, she joined Area Gallery on 10th Street in New York, and in 1960, held her first solo show there. Mason pursued her own unique artistic vision from early on in her career. In contrast to her mother’s geometric, hard-edge compositions, and her husband’s expressively romantic and colorful landscape-inspired imagery, she developed a distinctive form of intuitive, gestural abstraction featuring vivid layered color, and bravura brushwork, as well as indeterminate pours, always embracing the element of chance in her process.

Mason’s work often appears as a bridge between the Abstract Expressionists—many of whom she knew personally—and Color Field painters, like Helen Frankenthaler and Morris Louis, although her work never fits comfortably within any art-historical labels. Mason wholeheartedly believed in the transcendental possibilities of abstract painting. She relished experiments with analogous colors, and was partial to bright reds, oranges and yellows, often punctuated here and there with touches of blue or green. The textural nuances she achieved in the layering of pigment, and the unexpected intensity and luminosity of her color, unfailingly lead the viewer to a meditative place, an otherworldly realm. She would always deny guiding or manipulating the viewer in any way, though. Her paintings may suggest such a destination, but you have to get there on your own.

Winter's End, 1974, Oil on canvas, 36 x 54 inches.

Nari Ward

I first met Emily Mason when I was a young undergraduate student at Hunter College. I was enrolled in her beginners painting class, and wasn’t quite sure if I wanted to be an artist. Meeting her at that moment in my life changed everything. Emily always encouraged her students to experiment; and she would often bring in materials for us to work with. Her criteria for success wasn’t only making art, it was helping you find what worked for you. Her method of teaching was radically informed by empathy.

I remember being late for class because I was employed as a night shift security guard, and in the day often took a nap in the Hunter library before class, and overslept a few times. Instead of the usual teacher reprimand, Emily asked me where I slept and offered to come get me or send someone to wake me up. I was surprised by her pragmatic generosity and it motivated me to never come to her class late again. Making aesthetic decisions with emotive power while shining a light for others was a part of Emily’s self-assigned rigor, and this humanistic approach undoubtedly fueled her remarkable vision.

Part of Emily’s journey as an artist was to help others find their way through leading by example but also assisting when necessary. Over the years Emily became not only a mentor but also a friend. Even recently, at our last meeting, she was quick to tease me about how on my wedding day she was joyfully amused that my Uncle Felix was more focused on the temperature of the curry goat than the stated occasion. I will surely miss her wit, humor, strength, and unwavering love.

Sanford Wurmfeld

Knowing Emily Mason for over 50 years was a wonderful gift life presented to me. She was first and foremost a kind mentor together with her husband Wolf Kahn, both of whom, when we first met each other in Rome, introduced me to the possibilities that a committed and searching artist seeks. Emily was a lifelong friend whose art I was always thrilled to encounter. Her working methodology, based on years of ever expanding visual experience and knowledge of the history of art, allowed her to approach a surface in a most spontaneous manner and then to trust her reactions to the paint she first laid down in order ultimately to create astounding works—paintings which seemed to appear to a viewer as if produced by magic. For many years we were colleagues at Hunter College in New York, where Emily passed on her passion for painting in the most intelligent and nurturing manner producing generations of thankful and admiring students—some of whom became excellent artists themselves. Because of her teaching, her philanthropy, and most of all by her art, we are privileged to be continually influenced by Emily’s extraordinary legacy. Our world is a much less beautiful, magical, and kind place without her.

Steven Rose

Written to my one-year old Lennox, a month after the passing of our friend Emily Mason:

Dear Lennox,

We lost a beautiful spark this December. I expect you knew. You cried at the burial uncontrollably, which you never do. I expect you felt us all mourning, felt the immeasurable loss and maybe the sublime gift and responsibility that had been transferred. I like to think that she taught you how to see and how to wonder. When your eyes were just forming, weeks into this life, I introduced you to each painting in our house as I introduced you to the view of the linden trees and the sky outside our living room window. And you responded with no less awe. Eventually, your minute head jerks turned into audible gasps which would make us all giggle.

Later, when you could crawl on your own, I put you on the floor in her studio surrounded by Emily’s towering, vibrating paintings and you charged at them like a 20-pound bull, smiling and pointing. Emily looked into your eyes, and looking back at her was a kindred spirit, a spirit full of an unapologetic love for life, an insatiable curiosity for all things untested, and a little mischief. She has handed you the baton. Carry it well. You will embrace the sexy, naughty things, chuckle at a gentle but proper ribbing, and cherish a good sense of rebellion.

Emily so embraced rebelliousness; Exhibit A, her husband of 62 years, Wolf Kahn. Exhibit B through Z: each and every audacious move in every painting, oil on paper, and print she ever made. Wolf once said that Emily painted as a child sings, without reservation or having any plans. Watching your first steps, I would add that Emily lived (and painted) as a child learns to walk, with determination, abandon, and absolute revelry in the repetition. Her little bits of wisdom. Little internal rebellions. Pure idealism:

“Get the mind out of the way.”

“Let the painting speak.”

“If you are too attached to any one part, it is because you are neglecting something else.”

“Allow it more time.”

The result: heaps of dedicated hard work. Did I mention Emily never took a day off?

Towards the end of her life, she was more free and bolder than ever before. The compositions were so thin that sometimes the pigment was just dusting the tooth of the canvas to suggest its presence in the composition. She would simply leave it because the feeling in her tummy told her that the painting was finished.

The day after Emily decided she would forego any more treatment, she requested a trip down to Chinatown before heading back to her farm in Vermont. It was August and maybe one of the hotter days of the year and her body was tired after four months of chemo. Still, she wanted this. We made our way down to Canal Street to hit the fruit stands, the vegetarian Peking duck restaurant, the dried mushroom markets, and the congee shop. She couldn’t eat much by this time, but was ravenous. We collected. Yellow and red dragon fruit, lychees, two types of mangos she’s never seen before, strange plums that were labeled ‘Italian Grapes’ in Sharpie, ripe durian, bags of dried fish and mushrooms, and, of course, a photo of ox penis herbal soup. She posted the latter on her Instagram page with the caption “lunchtime." She loved to be naughty.

Emily Mason looking through her prints in her New York studio, 2015. Photo: Gavin Ashworth.

Jannis Stemmermann

In 1988 Emily was commissioned by the Associated American Artist Gallery to make an intaglio print edition. I was assistant to Catherine Mosley, Robert Motherwell’s master printmaker, who was contracted for the project. During the plate-making process Emily was dissatisfied with her proofs. On her own volition, she decided to experiment with a little known technique used by Joan Miró: painting carborundum grit and glue on the plate to create a matrix. The technique gave her flexibility and allowed her to work in a more intuitive way; a painterly print made on her own terms. In working closely with Emily to help her achieve the colorful veils that resulted in Soft the Sun, our friendship began.

After editioning Soft the Sun, excited by its results and potential for the carborundum aquatint process, Emily and I continued to work on our own. Nearly every Friday, from November to May, for over 20 years, Emily would show up at my studio door with hair in pigtails, a tote with freshly made plates, and a loaf of bread from the farmer’s market. The print studio would be ready for her with inks and stacks of prints in progress. I would make tea, slice and toast the bread, as we would chat and she made herself comfortable. Sometimes she would arrive with an idea that came to her while laying awake in the middle of the night—color choices for the day, coded in the hues of the silk turtleneck, cashmere sweater, and the pigtail ties she was wearing. With aprons on, we inked and wiped plates together. I operated the press—registering plates, adjusting pressure, laying paper, cranking—Emily waited for the thump of the plate passing through the press as she contemplated her next moves. By the end of the day, the studio wall was covered with fresh impressions, layers of newly added colors, veiled layering over dried ink from previous weeks or months. A print went in the “finished” pile when she felt there was nothing else that could be added.

Emily did not care for self promotion, but invested in fostering fellow artists. Being the daughter of early abstract painter Alice Trumbull Mason, and growing up in New York City, Emily always possessed clear mindedness about what it meant to be an artist and navigate a complex city. When we met, I was just out of art school and living in Williamsburg, Brooklyn and on my own. After working with each other for a few years, together Emily and I purchased a new Charles Brand press and set up shop in my Brooklyn studio. Simultaneously Emily encouraged me to continue making my own work. With her involvement in the beginning of the Vermont Studio Center [in Johnson, Vermont], she recruited me to be a resident; and that’s where my own work began to flourish.

Peter Schlesinger and Eric Boman

For nearly forty years, Emily Mason’s studio was located directly above ours in an originally manufacturing neighborhood where our building gradually attracted a diverse array of creative people. She bought the entire 11th floor, intending to share it fifty-fifty with her husband Wolf Kahn as studios. Wolf was not interested in half a floor and poo-pooed her buying it as a bad investment. Emily would giggle with delight years later when her real estate acumen was proven right. The south half of her floor instead became a greenhouse filled with orchids and other exotics that had to be trucked back and forth to Vermont each season.

As some of the first residents in a converted factory we got to know each other through issues of plumbing and the C of O, which then turned to gossiping about the eccentric artists in the building that included the fiber artist Lenore Tawney, whose incense wafted up the building, and the feminist artist, Hera.

Emily had a certain Yankee precision about her and you sensed that she kept a tidy palette, whether with pigments or people. This spirit also prevented her from repairing her radiators, preferring to place a shallow plate under each leak. The plates inevitably overflowed and the water would drip down to us. She turned off the offending radiators one by one, each time getting colder and colder as she asked the ever obliging super Agim to turn up the heat, making everyone else in the building boiling hot. Finally reason prevailed, the radiators were repaired and everyone was at peace.

Over the years we discovered that we shared with Emily an obsession with plants and nature; and we developed various traditions, like exchanging plants from our gardens, and going to the yearly Brooklyn Botanical Garden plant sale in the spring when the lilacs were in bloom. Emily gave us updates on the stature of a tulip tree sapling we’d dug up for her. Jars of jam and jelly she made in Vermont were given to us each fall. Another tradition was a cup of tea with Eric’s homemade cake in our apartment after Emily’s annual trip to Venice. One year, she brought us velvet gondolier slippers in fabulous colors that we still cherish.

Lucio Pozzi

During my first years in New York Emily Mason and Wolf Kahn were my family. I would often visit their apartment on 15th Street and invent fairy tales for their daughters before dinner. I first met them in Rome before moving to New York. We had exchanged studios. Wolf wore colorful ties and sweaters, the kids had knitted clothes, all made by Emily, a kind, beautiful and nurturing person. She was able to radiate her immense energy with understated grace, ever precise and smiling, vulnerable yet firm.

The colors her family wore were colors derived from her paintings. Her sweeping gestures of paint would support a thoughtful structure that she would have felt bashful expressing, or stressing too much. The exaggeration associated with most gestural painting would never enter her work. Ample fields of sometimes thin, sometimes slightly thicker layers of color alternated in wisdom, with quick calligraphies and smaller knots of pigment creating new chromatic territories that met or overlapped.

Attentive to every mode and mood, each of her works captivates my eye as something inevitable. In her work, it seems as if a certain red cannot but be placed where it is next to that particular blue, and blend under an orange tone before reaching a sharp mauve contradiction. While my eye scans the paintings, an enormous array of associations swirls in my mind, from landscapes to clouds, to entities that echo invisible existences, to vibrations that traverse my gaze. I register them only after they have filtered inside my own universe. I am thankful that nothing is imposed on me—her painting spurs me to reinvent it in my own terms each time I look at it.

Emily’s smile was open and fresh, ready to offer unsuspecting dialogue. The way she was able to be artist, woman, wife, and mother had the dignity of a deeply centered person, strong enough to be both supportive and independent. A veneer of melancholy added charm to her generosity.

In New York, Emily and Wolf brought Susanna Tanger and me, newcomers, around town, meeting the people they knew. Some evenings we would gather at Stan and Johanna VanderBeek’s loft. I remember the barber chair dominating the living space while looking at films. A few times Emily’s mother, Alice Trumbull Mason, like her daughter a resilient artist, came with them to our small loft on Avenue B and 6th Street with her captain husband, Emily’s father.

The modern painter who cares about the unforeseeable magic of painting by hand lives a life of resistance. S/he faces cyclical dismissals because the technique is ancient. But even worse, now s/he is also challenged by painterly concocters whose painting is fabricated from predisposed schemes. The gyrations of our ephemeral tastes seem to constantly endanger improvisational painting. Emily persisted in working unfettered, pursuing her painterly passion for unfathomable sensibility despite it all. Furthermore, she also faced down the difficulties her generation’s women artists had to work against since men, often their very partners, were encouraging a systematic preferential lane for themselves. Emily never sought to prove a point, never indulged in holding a rigid position. She is flying low and going far like the bird of I Ching.

With her passing, a central substance of my life is sealed into the mystery of time. Many are the friends that artists my age are losing, but Emily’s discrete and monumental absence builds a wall of void I’m having a hard time adapting to.

Carrie Moyer

Emily Mason’s paintings remind us that art is as much for the maker as it is for the audience. Her pleasure in the process is palpable, especially to us fellow painters who can picture her nonchalantly moving the materials over the surface with brush or finger. Nothing is precious. Over and over, her willingness to be experimental and playful with the oil paint and Gamsol resulted in fresh associations, feelings and insights into how color and light might operate on us. Such discoveries become a kind of joy to be shared by the artist and the viewer alike. I, too, am interested in sharing the thrill of optical and bodily sensation with my viewers. This is hard to do once, let alone over a career spanning seventy years and thousands of canvases. Brava Emily. Long may you play!

Louis Newman

I first met Emily Mason in her in a vast, light-filled Chelsea studio that had immense windows overlooking the skyscrapers of Madison Square and Midtown. Her studio was filled with numerous paintings and lots of plants; I suspect there were at least as many plants as paintings. The space was open and cheery, and on the walls were displayed a number of Emily’s richly colored works-in-progress. There were also works by various artists with whom Emily had a particular affinity: Hans Hofmann, Marsden Hartley, Arshile Gorky, and a watercolor of flowers by Charles Demuth. Though the studio was large, it felt very personal and surprisingly intimate, with some bits of clutter, and shelves crammed with art books. Mostly, I remember being surrounded by her paintings, emanating exhilarating color and light.

The year was 1997. For several decades, I had owned and operated the eponymous Louis Newman Galleries in Beverly Hills. Now I was in New York City, director of a newly opened gallery, MB Modern on 57th Street. In my eyes, I had arrived at the nexus of the art world. Emily Mason was to be the very first artist whose work I would exhibit there. By the end of the opening night of her solo show, every one of her works had been sold. This was the beginning of a working relationship with Emily, and a friendship spanning more than two decades.

In many ways, Emily introduced me to her New York. We often socialized outside of the gallery and the studio. Emily and her husband Wolf Kahn were always intellectually curious and connected. They brought me into their world—from invitations to chamber music concerts to lectures, exhibitions, and artist talks. Occasionally, we even attended memorial services celebrating the lives of important individuals that they had known, but who I had never had the privilege of meeting. Through Emily, my world was expanded and greatly enriched.

Emily was always refreshingly straightforward and honest. We trusted each other, and because of her approach to both life and art, working with her would be transformative. She possessed an inquisitive, embracing, and totally engaged spirit and she communicated those qualities in her paintings. Emily’s work was not about angst or high drama. She was at peace with her universe. And there was always playfulness in her work that is rarely seen in abstract painting—all enhanced by Emily’s remarkable grasp of the emotional possibilities of color.

In October 2015, I was invited to become director of Modernism and Contemporary Art at LewAllen Galleries in Santa Fe where the “Emily Mason tradition” continues. Over my many years as an art dealer, I have helped numerous artists with their careers. Emily was the one artist who I feel made my career. Through Emily, I learned to better appreciate the needs of the artist, and to address those needs. I believe that she helped make me a more thoughtful and sensitive dealer. I understand from those present that on her final day Emily recited one of her favorite poems by Emily Dickinson. The poem captures much of the magic of Emily the artist, and the joyousness she has left in her wake.

She Sweeps With Many-Colored Brooms

She sweeps with many-colored Brooms—

And leaves the Shreds behind—

Oh Housewife in the Evening West—

Come back, and dust the pond!

You dropped a Purple Ravelling in—

You dropped an Amber thread—

And now you've littered all the East

With duds of Emerald!

And still she plies her spotted Brooms,

And still the Aprons fly,

Till Brooms fade softly into stars-

And then I come away—

—Emily Dickinson

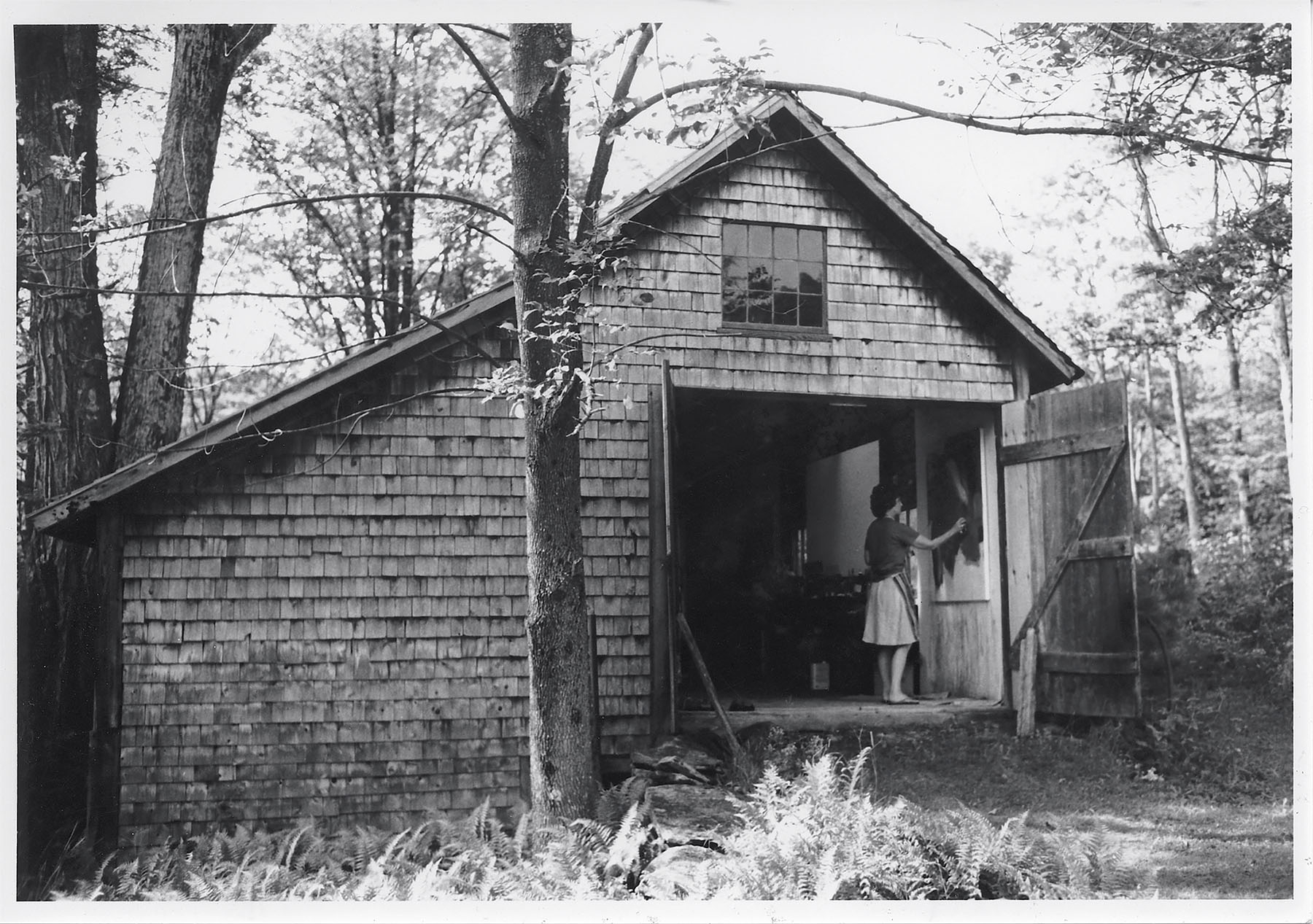

Emily working on Midnight Slant in her Vermont studio, 1986. Photographed by Jean E. Davis.

Eric Aho

Backed by the slimmest of introductions, I showed up at Emily Mason and Wolf Kahn’s hilltop farmhouse in Vermont in the summer of 1989. Fresh out of art school, I had just landed in Vermont and had begun to paint. Ostensibly, I went to meet Wolf, but it’s Emily who I remember when I think of that day. Stepping out of her studio, wearing an apron, her hair in those disarming pigtails, she greeted me with that enormous smile and a warm and simple hello. Was I the imposition I had feared? Her well-practiced welcome—to be sure there have been many other young artists in Maine, Italy, and New York who had similarly wandered into their art camp—was so sincere that it instantly put me at ease. She served lemonade, fresh bread, and her award-winning jam.

While we waited for Wolf to join us, we looked over the hills and just talked quickly, alighting on a shared interest in mushroom foraging (a Finnish thing for me, and for Emily, the very symbol of interconnectedness in nature). If the farmhouse—untouched since the mid 19th century, with only a wood stove for heat—reminded of the past, sitting with Emily was the here and now. Her unrushed engagement insisted that being in the present was what mattered. Eventually, I came to see her casual ease as a hallmark of her painting, and of Emily herself.

But at the time, her painting somehow initially made me uneasy. I’d been taught to be suspicious of beauty. Maybe her paintings were too beautiful. Looking back, I think they were just way ahead of me; they tested my biases and preconceptions. Fear and beauty lie at the core of the sublime. I hadn’t yet understood that joy could be a subject of painting—or that joy and sorrow might even, at times, share the same palette.

Soon enough, I caught on. Emily’s 1993 exhibition at nearby Marlboro College was a full sensory experience. Her unique language of indirect poetic assertions, through poured, spilled and brushed color guided by action and deliberate accident, was exciting and pointed to the human register her painting occupies. My Pleasure, a work from that time, sets a defining multi-layered tone of Emily’s playfulness and purpose.

From a family of artists, Emily was already swaddled in a mature experience of abstraction. After all, her sensitive works reveal her very personal arena of habits, desires, wishes, failures, dreams, and hopes. How wonderful it must be to paint without pretense, to be aware of, yet, free from the tyranny of fashion. How wonderful it must have been to be deeply informed by painting’s lush antecedents, to accept one’s own doubt, struggle, and the visitation of success—and to work with one’s senses fully engaged. Encountering Emily Mason’s paintings was not unlike encountering Emily herself.

Bright and warm as many of her works are, they’re not exactly about light, nor of the sun, precisely. As I came to know Emily better, her paintings became her proxies, pulsing like bioluminescent optic phosphenes, similar to the miraculous neural show of color we see when our eyes are closed. The incandescence is internal—more human than phenomenological—quirky, intense, sensual, and unpredictable meditations on experiences, passing thoughts, moods, and temperatures of feeling. Her paintings are deceptive, not unlike her beloved fungi—delicacy and danger hiding in plain sight—and like Emily’s petite stature, conceal more power and depth than they might outwardly appear. Rarely are her paintings bigger than she could carry—her arm span always tethering them to a human, personal scale. After all, a canvas needn’t be ten feet wide when the feeling applied to it is beyond measure.