JIM ISERMANN | ARTILLERY

Gallery Rounds: Jim Isermann

19 JUNE 2024

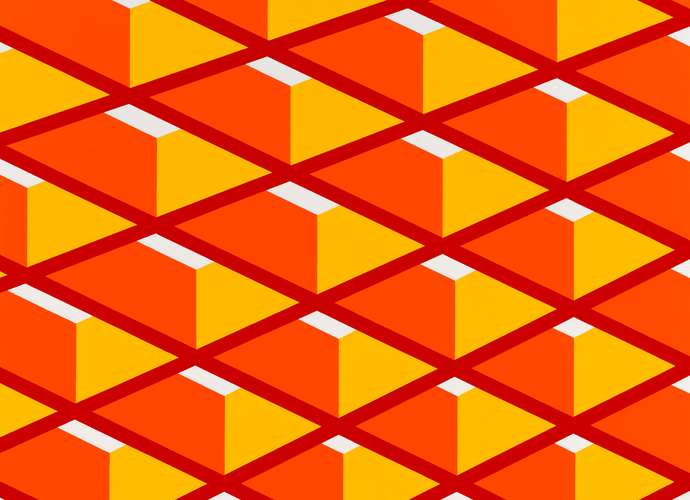

Untitled (4,4,4), 2019,

Acrylic paint on canvas over aluminum panel, 48 x 48 inches

Back at the front desk, the McEnery Gallery has a gorgeous hardcover catalog for sale, which I expected, and Isermann bath towels, which I didn’t. I bought the towels, and on my way back to the car, I noticed a woman in a brightly colored geometric dress. “Are you wearing an Isermann?” I asked her; she laughed and said no. Later, back home, putting the towels in my bathroom, I remembered her and felt pangs of desire for objects that don’t yet exist. I want to see women wearing Isermann dresses and carrying Isermann handbags. I want to wear Isermann T-shirts, dress shirts, pants and jackets. I want to drive into an Isermann sunset in an Isermann car.

James Cushing —

Los Angeles, CA: Pacific Design Center Design Gallery,

‘Jim Isermann: WRAPTURE,’ 2 May 2024 - 29 June 2024.

Image: Joshua White / JWPictures. Courtesy of the artist and

Miles McEnery Gallery, New York, NY

As with any Moscoso poster, the “meaning” in Isermann’s work is inseparable from its function in an implied context in which an old hierarchy of values is gently dismantled. The hierarchy Isermann takes apart is that which holds the “decorative arts” like patterned wallpaper to be, by definition, secondary to the more “substantive arts” like landscape or portraiture. The decorative is domestic, home-bound, and of limited interest, operating as it does outside the pale of art history; one becomes used to reading the adverb “merely” before it. The decorative is implicitly feminine or “queer” if a man does it. It represents a withdrawal from the existential battle for self-expression central to modern sensibility.

After spending even fifteen minutes inside “Wrapture,” it’s simply impossible to take that hierarchy seriously. The McEnery Gallery gets some credit for that, having arranged for Isermann’s work to take up two whole floors and the staircase between them. At the desk, one is startled by the sheer size of the patterns (decals painstakingly applied to the walls), and their monumentality immediately cancels any associations with domesticity.

One climbs the stairs and gapes. Again, the walls themselves have gotten the full Isermann treatment: one is mirror-silver with big white dots, the others brightly patterned (decals again). Wallpaper? Maybe. What’s the opposite of “merely”? Isermann’s sheer joy in color and bravado in design please the eye like Hockney’s blue pools and green gardens do.

Untitled (hole painting) (2987), 1987,

Enamel paint on panel, 48 x 48 inches

Against these nonstop walls, acrylic paintings display bright primary colors arranged in vibrating geometric patterns. The longer I examined one, the more it seemed to move and hum, flip and warp like an ecstatic kaleidoscope. (“Rapture,” get it?) Although the show surveys 35 years of work, no one painting is given precedence over any other. It’s all one piece; Isermann’s obsession with pattern and color is his art’s signature, and his trust in them as sources of wonderment is the essence of his art’s integrity.