Hans Hofmann

"Riches of a City: Portland Collects" at The Portland Art Museum, 5 February – 22 May 2011

If this collection is elegant and aesthetically rewarding, it also includes very little that is raw or confrontative. Still, the uncomfortable is there, if mostly in stylized form. A small, savage, technically gorgeous 1844 lithograph by Delacroix shows a ravenous lion devouring the horse it's just taken down. The African American artist Jacob Lawrence's 1937 painting Christmas Dinner depicts a family seated around the table, praying, while a framed painting behind them shows a corpse hanging from a noose. And two relatively recent photographs -- Iran-born Shirin Neshat's quietly provocative I Am Its Secret, a close-up of a woman whose face is delicately painted so it looks almost like a target, and Vietnam-born Dinh Q. Le's large double image of a street execution in Vietnam and a scene from the Oliver Stone movie "Born on the Fourth of July" - allow the world of danger and violence to come rushing in.

Sometimes, home is where the heart skips a beat.

Bob Hicks —

The Portland Art Museum's sprawling new exhibition, "Riches of a City: Portland Collects," announces its intention the moment you walk in the door: It's about the warmth and pleasures of domestic life - if not always in the art itself, at least in where it comes from.

Staring out at you from the get-go at the exhibit's main-floor entrance is Roy Lichtenstein's giant 1992 screenprint Wallpaper With Blue Floor Interior. With its strangely squiggled carpet, sharp modern angles, signature polka dots and plush sofa, Lichtenstein's iconic print suggests sly contemporary chic and immense comfort. Kick off your shoes, metaphorically at least, and relax. You're behind closed doors.

You'd have to have a pretty big living room wall to hang that Lichtenstein or a handful of other large pieces in this 237-work show. But for the most part, the scale is intimate. From 4,000-year-old Chinese storage jars to Clifford Rainey's luminescent Ghost Boy contemporary glass torsos, with stops in between for artists as separated in time and style as Lucas Cranach the Elder, Durer, Tiepolo, French Impressionist Berthe Morisot, 20th-century protean man Pablo Picasso, photographer Nan Goldin and modern large-scale calligrapher C.C. Wang, this is art you can live with -- and in fact, art that a lot of Portlanders do live with.

Eighty-three of the city’s collectors have loaned pieces from their private collections to make up this expansive survey of what amounts to a highly arranged snapshot of the city’s collective visual taste in 2011. The focus? A fittingly urban variety and vitality, with high aesthetic value, historical depth and surprisingly few rough edges: Call it a comfortable domesticity.

Chosen over a year by the museum’s curatorial staff and then shaped for presentation by chief curator Bruce Guenther, “Riches of a City” includes work in six main areas: historical European and American art; European and American silver; 20th century art; historical and contemporary Asian art; photography; and prints and drawings.

Those areas roughly represent the breadth of the museum’s own major collections, minus a couple of key focuses: Native American art and Pacific Northwest art. The museum is seeking a new curator for its Native American collections, and has other Northwest shows in the pipeline.

In its 117 years, Guenther says, the museum has assembled a collectors’ overview show about 20 times. There are many good reasons to do so, and one that stands out: Museums, especially regional museums such as Portland’s, get most of their permanent artworks from collectors’ donations. The relationship between curators and collectors is complex and, ideally, beneficial to both. Curators give a lot of advice and often help shape private collections. In return, they hope that at least parts of those collections eventually will be donated to the museum.

It’s a back and forth. And I think that’s a good thing,” says museum director Brian Ferriso, who calls curators “the engines of the institution.”

MIXING AND MATCHING

The exhibition's title comes from a quote by early Oregon lawyer/writer C.E.S. Wood, who was also one of the museum's founders: "Good citizens are the riches of a city." The breadth of the survey suggests that some interesting new collectors have joined the old guard in recent years, and the names on the lender list (many have made their loans anonymously) also point out the fragility of stewardship. Three major collectors - Carol Stam Hampton, Tom Holce and Ed Cauduro - have died recently.

Making visual sense of such a freewheeling exhibition isn't easy. It could simply be divided into rooms according to collection. And some of it is: The Asian collections, for instance, tend to be in their own spaces, speaking primarily among themselves in a conversation that ranges from antiquity to spirituality to the pleasures of craftsmanship and form. Highlights range from the exquisite classicism of a 15th-century Jiangxi Province Chinese porcelain vase to a beautifully scripted 16th-century Iranian double-page leaf from a Quran to some sinuous contemporary Japanese basketry by Honda Syoryu and others.

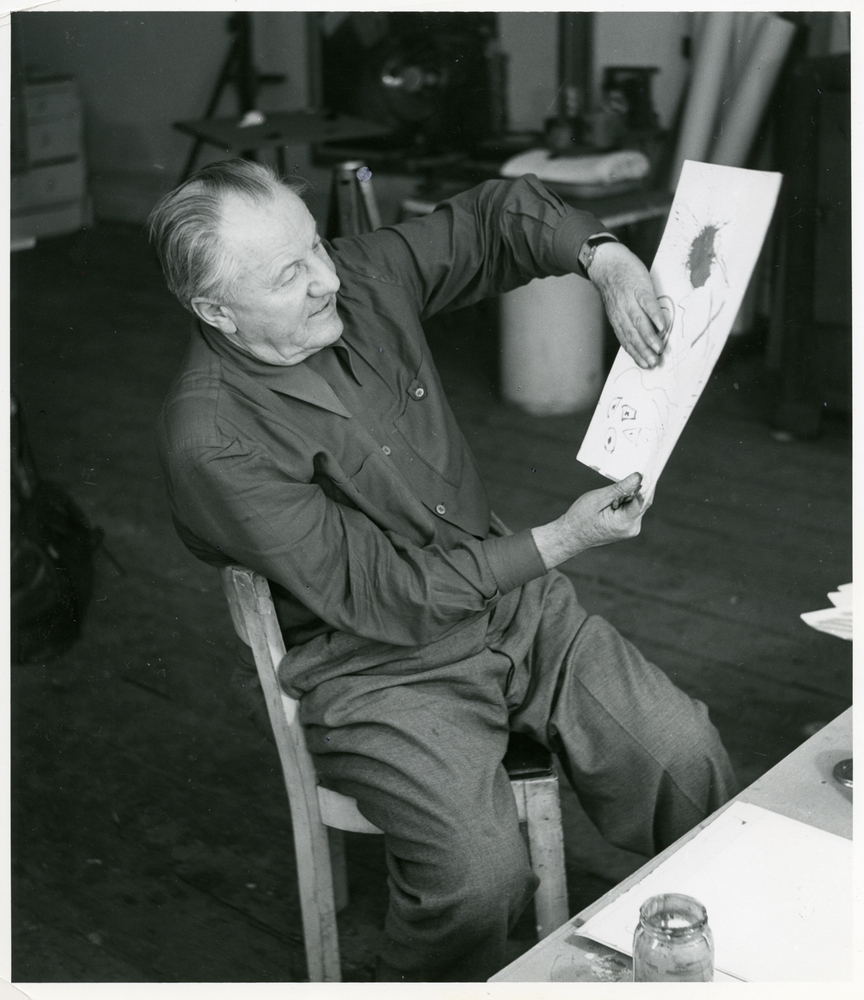

But in other areas Guenther has taken a more intriguing approach, letting suggestions of compatibility and interesting juxtaposition guide his hand. Joining the big Lichtenstein in the opening space, for instance, are other modernists such as Robert Rauschenberg, sculptors Donald Judd (a sleek and lovely minimalist gesture) and Duane Hanson (the slumped and stolid Dishwasher, a fine example of his psychologically disorienting hyperrealistic human figures), but also some splendid Danish silver pieces from the Georg Jensen firm. Besides sharing a modernist bent with the other works, the silver sets also quietly underscore the exhibit's domestic theme. This grouping also includes a couple of prominent mid-20th-century painters who were as noted for their teaching as for their art: Hans Hofmann on the East Coast and Clyfford Still on the West.

The show's mix-and-match approach allows certain kinds of works to cluster together, but also makes for a comfortable easiness, allowing sculptures, paintings, photos, prints and drawings to rub shoulders naturally. It's a little like a cocktail party with a good mix of guests: After a while, everyone just seems to fit.

Even works that seem atypical can tell fascinating historical stories. A still life by Gustave Courbet, for instance, has none of the realist astonishment or transgressive energy of his most famous work: It seems as if it could have been done by almost any moderately talented still-life painter. But Courbet painted it after the Paris Commune, when he was in prison for six months on political charges. "His family brings him fruit to eat, and he paints the fruit because that's what he can paint," Guenther says. "Seventeen still lifes, I think, and then he was done."

Photographs range broadly from the classic (Berenice Abbott, Ansel Adams, Ruth Bernhard, Imogen Cunningham, Alfred Stieglitz, Robert Mapplethorpe, Edward Weston) to the pioneering (an oddly humorous series of female nudes in motion by Eadweard Muybridge) to the buoyantly inventive (Dieter Appelt's image of a man breathing on a mirror) and the downright comically weird (Joel Sternfeld's 1982 Exhausted Renegade Elephant, Woodland, Washington).

ENERGETIC TO EERIE

"Riches of a City” shows a good deal of strength in its late 19th and 20th century pieces, including paintings, sculptures and works on paper. There’s a lovely little Degas bronze dancer, bold posters by Toulouse-Lautrec and the Czech artist Alphonse Mucha, and a march of lovely pieces by Cezanne (one of his blue-tinged lithographs of male bathers), Gaston Lachaise (a charming, quick pencil drawing of a female nude from the back), Picasso (a 1959 lino cut of one of his serene bacchanals), and Chagall (a dreamlike gouache village scene in blue). The category is expansive enough to include a copy of Ben Shahn’s quietly moving litho Beside the Dying, from his 1968 “Rilke Portfolio,” and Richard Serra’s roughly layered, forcefully energetic 1991 etching and intaglio print Iceland.

One of the show’s most intriguing juxtapositions is an 1896 litho by Edvard Munch of an eerie, cadaverous lovers’ embrace next to a pair of Picasso’s exquisitely upbeat mythological romps: from death to life in one quick flick of the eye. And one wall is dominated by Andy Warhol’s iconic 1970 series of 10 silkscreen Mao prints. (“The image of the greatest enemy of capitalism became the collecting toy that every rich man had to have,” Guenther wryly notes.)