Patrick Wilson

"A Lesson in Geometry," WhereTraveler, New York City

27 May 2015

A Lesson in Geometry By Jean Cohen

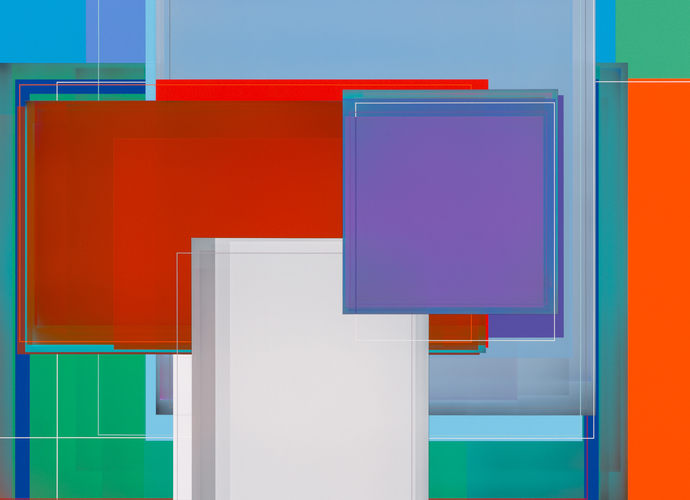

Listen to Patrick Wilson, see his new paintings in Chelsea (at Ameringer | McEnery | Yohe) and take away some art history. What Wilson has done for 20 years—works of elegant color, flatness and right angles—may seem, at first, the offspring of other art born out of geometry since the mid-20th century. But paintings by Wilson look like no one else's.

Sure, a computer could generate infinite variations of rectangles, bands and pinstripes, but credit Wilson’s dazzling precision to his studio life and discipline. He places each canvas, stretched on heavy board, atop sawhorses and applies acrylic paint with a roller for opaque fields or a drywall blade for transparent films. He sticks to “human-scale,” he says, the size of a work “dictated by the length of my arm.”

At any one time, Wilson may have as many as six paintings-in-progress. If he reaches a stopping point with one, he moves to another. Each emerges from a gradual accretion of layers and from rethinking unwanted effects that he then conceals or reduces to seams or slivers. Wilson achieves complexity and these mysterious planar shifts not by hewing to a simple matrix (Stella had his squares, Noland his targets), but by allowing the given elements to evolve with moment-to-moment choices and revision.

His obsession with squares and rectangles might seem a denial of such spontaneity. But he insists, “I work intuitively. I have no Albers color theory to prove, no predetermined plan to illustrate. Like a musician improvising, I let the painting lead the way.” Knowing that this sounds a bit like Jackson Pollock and the Ab Ex guys, Wilson cleverly describes his approach as “slow-motion action painting.”

Ameringer | McEnery | Yohe shows recent works ranging from 22 inches square to 72 inches long by 67 high. Wilson has given them all titles, some poetic (“Kimono”), some place names (“Berkeley”), a few tongue-in-cheek (“San Andreas” with obvious fault lines). “I use titles,” he says, “but I don’t want to limit a viewer’s point of entry, to stop a free association with what’s pure abstraction.”

A few titles play with art history. For example, “Field Day,” with subtle grays and one right-angle red, perhaps alludes to the timeless genre of Color Field, and “Swamp Boogie” may or may not throw a millennial kiss to the geo-great-grandfather Mondrian and his “Broadway Boogie Woogie.” “Fog Scissors” recalls an Ocean Park (California) skyscape by Richard Diebenkorn. Wilson attaches that title to a work that looks as if it’s been cut and recomposed from the “atmosphere” of the earlier painting.

Wilson places himself in the lineage of the “Hard Edge” fathers of California abstraction, artists like Frederick Hammersley, John McLaughlin and, one he knew, Karl Benjamin. For him, “These are very important artists and, to this day, under appreciated.” Now Ameringer | McEnery | Yohe represents their East Coast contemporary Gene Davis, the late “color school” artist Wilson admires but never met. A stripe painting or two by Davis can likely be glimpsed in a back room.

For years, I only saw Davis’ paintings in books,” says Wilson. “Later I found them awe-inspiring and felt swallowed up by their scale.” The two artists share something as basic as the use of masking tape (to achieve an almost perfect hard edge) and as crucial as the reliance on whim. Like Davis, Wilson surprises with intervals of color and an optical push-pull that insists each painting be read in time.

No doubt Davis, whom this writer knew well, would acknowledge the similarities even as he pointed out the deviations. Davis himself attributed his signature stripe to the “zip” of the older master Barnett Newman. He often recalled with delight that Newman had encouraged him and once addressed their mutual use of the stripe, saying "You did something different with it." That’s the reassurance Davis would pass now to an indirect heir as masterful as Patrick Wilson.

Patrick Wilson opens May 28 with the artist present at a reception, 6-8 p.m., and remains through July 3. A catalog features 19 color plates and an essay by Stephen Westfall.

Ameringer | McEnery | Yohe, 525 W. 22nd St., 212.445.0051, www.amy-nyc.com

Jean Lawlor Cohen, former editor of Where Washington D.C. magazine and a part-time resident of New York City, reports on the arts and dining.

http://www.wheretraveler.com/new-york-city/lesson-geometry

Image: Patrick Wilson, Swamp Boogie, 2015, Acrylic on canvas, 49 x 59 inches, 124.5 x 149.9 cm